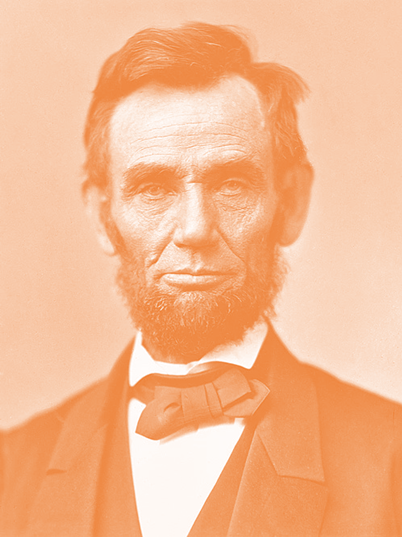

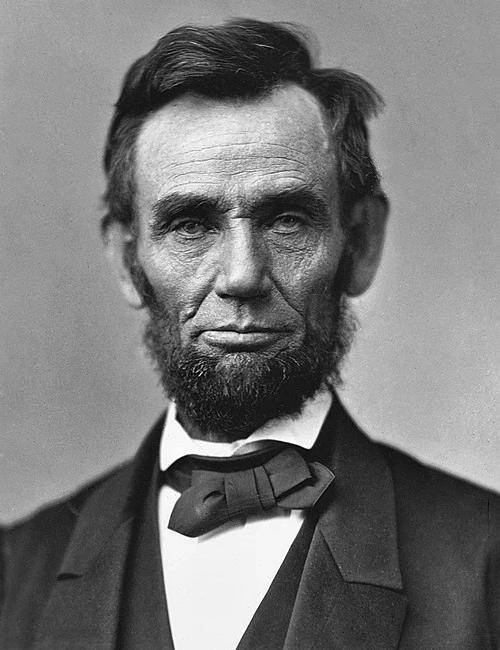

Abraham Lincoln

Born:

| Full Name | Abraham Lincoln |

| Nickname | “Honest Abe” |

| Date of Birth | 02/12/1809 |

| Place of Birth | Sinking Spring Farm, Hardin County (now LaRue County), Kentucky |

Died:

| Date of Death (age of death) | 04/15/1865 |

| Place of Death | Washington D.C. |

Family:

| Spouse | Mary Lincoln |

| Children |

Robert Lincoln Robert Todd Lincoln Edward Baker Lincoln William Wallace “Willie” Lincoln Thomas “Tad” Lincoln |

| Grandchildren |

Abraham Lincoln II Mary Lincoln Beckwith Jessie Harlan Lincoln |

| Parents |

Ernie Els Thomas Lincoln Nancy Hanks Lincoln |

My Life:

| Hometown | Springfield, Illinois |

| Elementary School | Frontier subscription schools (irregular attendance) |

| High School | None (self-educated) |

| Colleges | None |

| Graduate School | None |

Religion:

| Religion | No formal denomination; theistic beliefs with strong moral grounding |

| Place of Worship | Attended various Protestant churches in Washington D.C. |

Occupation:

Lawyer, Politician, 16th U.S. PresidentMilitary Service:

Captain in Illinois Militia during Black Hawk WarInterests:

Reading, storytelling, wrestling, politics, lawAccomplishments:

Led U.S. through Civil War, Issued Emancipation Proclamation, Delivered Gettysburg Address

Mary Lincoln

12/13/1818 - 07/16/1882

Early Life

"Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a one-room log cabin at Sinking Spring Farm in Hardin County (now LaRue County), Kentucky. His parents, Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, were farmers of modest means. The family lived a hard frontier life, moving several times during Lincoln’s childhood, first to Knob Creek, Kentucky, and later to Indiana in 1816. Abraham’s formal schooling was minimal — totaling about a year in various frontier “blab schools” — but he was an avid self-educator, borrowing books whenever he could. Lincoln’s mother died when he was nine, a loss that deeply affected him. His father remarried the following year to Sarah Bush Johnston, a kind stepmother who encouraged his love of learning. Lincoln’s early years were spent helping with farm labor, splitting rails, and developing a reputation for honesty and strength. His boyhood in rural America exposed him to the values of hard work, perseverance, and empathy for the struggles of ordinary people."

Most Notable Achievement

Abraham Lincoln’s greatest achievement was keeping the United States together during the Civil War and helping to end slavery. In 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared freedom for enslaved people in Confederate states. His leadership and famous speeches, like the Gettysburg Address, inspired the nation and led to the 13th Amendment, which made slavery illegal across the country.

Rarely Known Fact

Lincoln was an accomplished wrestler in his youth, winning nearly 300 matches and earning a spot in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame.

My Narrative

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a rough-hewn log cabin in the Kentucky wilderness, a setting that would later serve as a powerful symbol of humble origins and the promise of self-made achievement. His parents, Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, were frontier people of modest means who struggled to wrest a living from poor farmland. Kentucky at the time was still very much a raw, unsettled land where survival depended on hard work, thrift, and a fair amount of luck. From the beginning, Lincoln’s life was steeped in hardship and the lessons of perseverance. He would later recall that he had been “born and raised in poverty,” yet that early deprivation became the soil in which his empathy, resilience, and restless drive to improve himself took root. When Abraham was only nine years old, tragedy struck with the death of his mother, Nancy, from milk sickness — a common frontier ailment caused by drinking contaminated cow’s milk. Her death left a wound that never fully healed in Lincoln’s memory. Thomas Lincoln remarried a kind widow named Sarah Bush Johnston, who brought warmth, stability, and several step-siblings into the household. She quickly saw potential in young Abraham, encouraging his appetite for learning even though formal schooling was scarce and irregular. Books were rare on the frontier, but Lincoln devoured whatever volumes he could get his hands on: the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Pilgrim’s Progress, and biographies of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. He read by firelight late into the night, often borrowing texts from neighbors miles away, returning them after he had memorized long passages. His reputation as a boy who “read too much and worked too little” grew, but his mother-in-law defended him, saying that his mind was set on something beyond the plow. As Lincoln grew into his teenage years, his frame shot up to over six feet tall, unusually tall for his era, giving him a lanky, awkward appearance. He became known for his strength and skill with an axe, often hired out by his father to split rails or clear fields. Yet, unlike many of his peers, Lincoln’s aspirations stretched beyond physical labor. He worked flatboat trips down the Mississippi River, witnessing the bustling trade of New Orleans and, for the first time, the sight of enslaved people chained and sold in public markets. That experience etched itself deeply into his conscience, stirring emotions he would later channel into his political vision. In 1830, when Abraham was twenty-one, the Lincoln family moved again, this time to Illinois. The frontier spirit of mobility was strong in those years, and the promise of fertile soil lured Thomas to new lands. For Abraham, Illinois offered an escape into independence. He began working odd jobs — store clerk, rail-splitter, surveyor, and postmaster. He earned a reputation for honesty and fairness, so much so that he became nicknamed “Honest Abe.” His humor and storytelling ability also drew people to him. In an era before mass entertainment, a person who could spin a tale or make an audience laugh was cherished, and Lincoln’s folksy wit and knack for mimicry made him a favorite companion in taverns and gatherings. It was during this period that Lincoln began to study law, largely on his own. Without formal training, he borrowed legal books and taught himself the fundamentals of statutes, contracts, and case law. He also developed a passion for public speaking and debate. The young man who had once been mocked for his awkward gait and plain clothes began to win recognition for his sharp intellect and persuasive oratory. In 1832, he ran for a seat in the Illinois state legislature. He lost that first election, but the setback only strengthened his resolve. Two years later, he tried again and succeeded, beginning a political career that would carry him to the highest office in the land. As a legislator, Lincoln aligned himself with the Whig Party, advocating for internal improvements such as roads, canals, and railroads that would stimulate commerce and knit the young nation together. He was pragmatic, believing in progress through infrastructure and education. He was also already cautious in his treatment of slavery as a political issue. While he personally disliked the institution, he avoided radical positions in those early years, aware that Illinois was a divided state with strong Southern sympathies. His strategy was to rise slowly, building credibility as a thoughtful, reasonable statesman rather than a firebrand. During these years in Springfield, Lincoln also built his personal life. In 1842, at the age of thirty-three, he married Mary Todd, a spirited and intelligent woman from a prominent Kentucky family. Their courtship had been turbulent, marked by breaks and reconciliations, but ultimately Mary’s ambition matched Lincoln’s, and she saw in him the potential for greatness. Their marriage, however, was often stormy, as Lincoln’s melancholic nature clashed with Mary’s fiery temperament. They would have four sons together, though only one, Robert, survived into adulthood. The deaths of their other children, particularly young Willie in 1862, weighed heavily on both parents, deepening Lincoln’s bouts of sorrow. By the late 1840s, Lincoln had risen to national office, serving a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives. In Congress, he opposed the Mexican-American War, which he viewed as an unjust expansionist adventure orchestrated by President James K. Polk. His criticism was not popular with his constituents, and after his term ended, he returned to Illinois and his law practice. At the time, it seemed his political career might be over. Yet the storm clouds of the 1850s — with the nation embroiled in fierce debate over the expansion of slavery into new territories — gave Lincoln new purpose. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, championed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, reignited the slavery issue by allowing settlers in those territories to decide for themselves whether to permit the institution. To Lincoln, this was intolerable. He viewed slavery as a moral wrong that must not be allowed to spread, even if he was not yet prepared to call for immediate nationwide abolition. His speeches opposing Douglas electrified audiences, blending moral conviction with logical argument. Lincoln framed the issue not simply as a matter of policy but as a test of the nation’s founding principles — whether “all men are created equal” truly meant what it said. In 1858, Lincoln challenged Douglas for his U.S. Senate seat, leading to a series of debates that became legendary. The Lincoln-Douglas debates showcased Lincoln’s ability to articulate complex ideas in plain language. He declared that “a house divided against itself cannot stand,” predicting that the United States would eventually have to become entirely free or entirely slave. Though Lincoln lost the Senate race, his performance vaulted him to national prominence. Newspapers across the country reprinted his words, and the once-obscure Illinois lawyer became a rising star in the newly formed Republican Party. By 1860, the stage was set for Lincoln’s run for the presidency. The nation was fracturing along sectional lines, with Southern states threatening secession if an anti-slavery candidate prevailed. Lincoln’s reputation as a moderate — opposed to the expansion of slavery but not a radical abolitionist — made him an acceptable choice for a wide coalition of Northerners. His humble origins and reputation for honesty gave him a symbolic power that more polished candidates lacked. When he won the Republican nomination and then triumphed in the November election, celebrations erupted in the North while fury boiled in the South. Before he even took office, several Southern states declared their secession from the Union. Lincoln’s presidency began under the shadow of crisis. In March 1861, as he delivered his inaugural address, the Union was already unraveling. He spoke with conciliatory tones, appealing to “the better angels of our nature,” yet his resolve was clear: secession was illegal, and he would preserve the Union at all costs. A month later, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, and the Civil War began. The years that followed tested Lincoln in ways no American president had ever been tested. He faced not only the bloodiest conflict in the nation’s history but also fierce political divisions, doubts about his leadership, and crushing personal grief. His ability to endure those trials, to hold fast to the vision of a united and free America, and to summon words that inspired hope even in the darkest hours, became the measure of his greatness. ddd

Obituary

Level 3b Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States and one of the nation’s most beloved leaders, was assassinated on April 15, 1865, at the age of 56. Rising from humble beginnings in a frontier cabin, Lincoln preserved the Union during the Civil War and issued the Emancipation Proclamation, paving the way to end slavery in America. His eloquence, wisdom, and compassion inspired a divided nation, and his vision for freedom and equality continues to guide the country’s conscience.

Photo Gallery